‘Conventions of Ecological Urbanism’ makes painfully real the urban sustainability metrics used by municipalities for zoning, design, funding, and revitalization

Real Urbanism

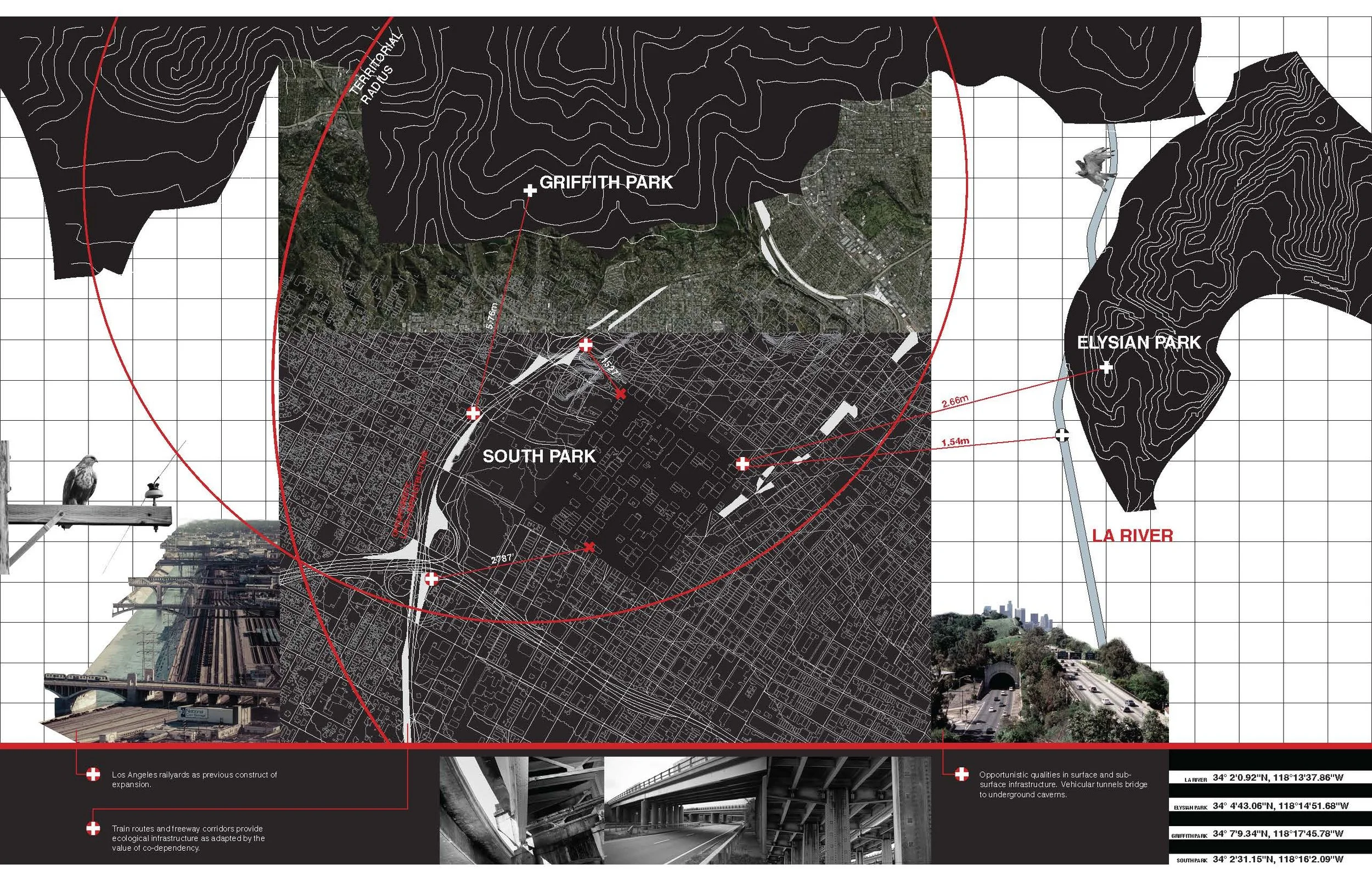

Ecological urbanism would have us believe that the standards and aesthetics associated therein are the epitome of ecologically minded, functional design. However when an individual of academia challenges these conventions, one finds a checklist of physically impossible tasks to achieve. Status quo technology cannot meet the demands of ecological urbanism and therefore can be nothing more than a school of thought from which an individual may choose to approach a design problem. What might a design problem which exists in the requirements of ecological urbanism yield when the very principles that support it are questioned? South Park serves as a laboratory for an urban experiment that leverages the truth of an ecological city. This district of downtown Los Angeles is poised to accept these interventions based on its contextual variants and ample infrastructure. What kind of systems can be adapted and, perhaps, introduced into South Park that will allow this district to function as a brutally honest ecosystem? Disbelief must be temporarily suspended as certain values of urban design are insufficient to express the complexity of the proposed ecologies of South Park.

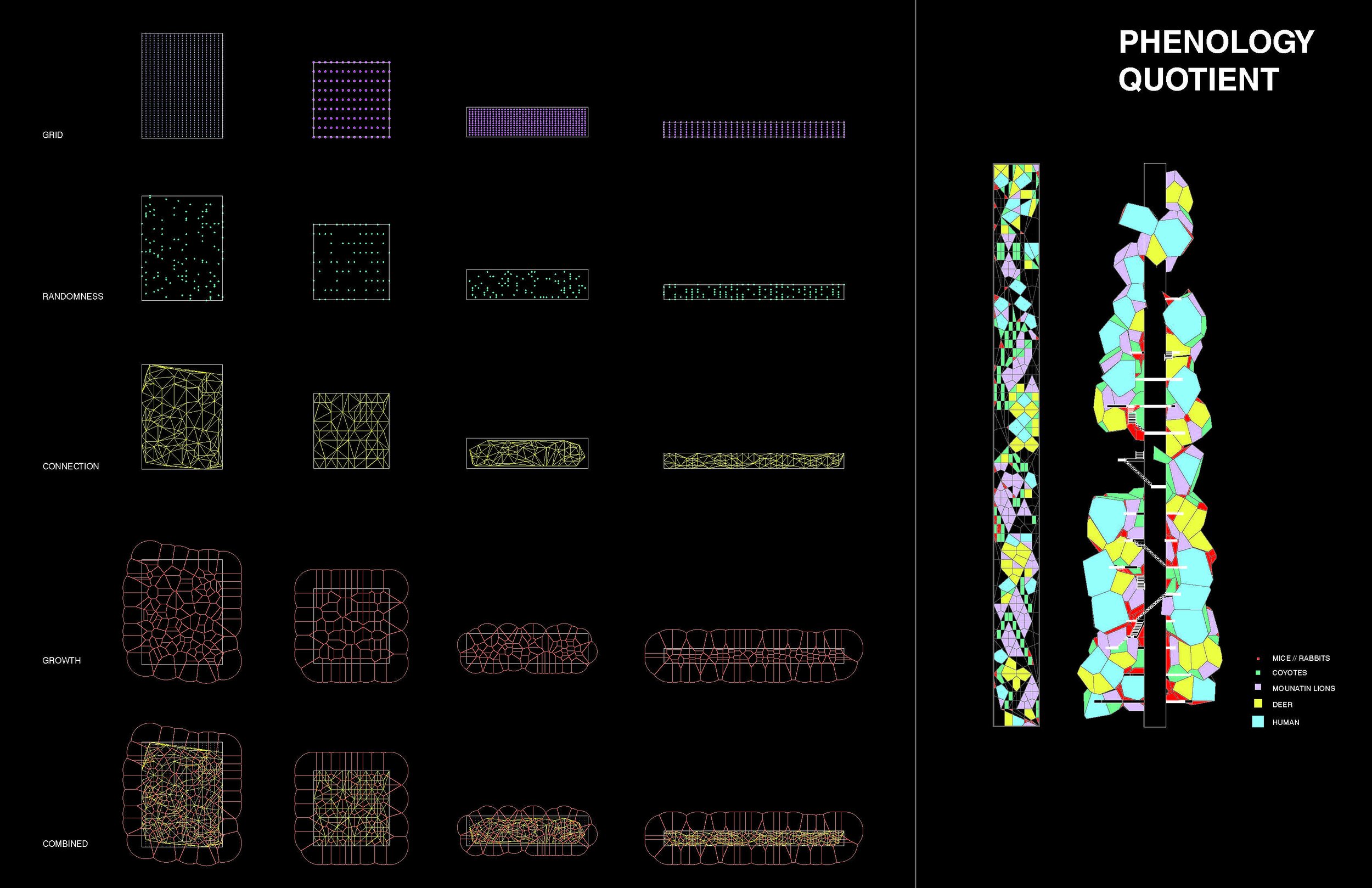

Plant and animal systems are proposed aspects of traditional design that are rarely represented accurately. In nearly every urban example, “nature” exists separately from the built, human-inhabited environment. For these systems to function properly, they must be integrated to access the same resources and occupy the very same space as humans. The success of these adaptive systems can no longer be measured in conventional means of value, but rather in metrics that express the adaptability and the inherent success and failure of these systems. Death and decay are integral parts of ecological systems that are often hidden and rarely seen in the urban environment and when it is, it is seen as dirty, dangerous, and undesirable. When these systems are allowed to exist in true symbiosis, processes of reciprocity will be the new determining factors of the benefits and opportunities of an urban environment, namely, South Park. A new density can be imagined when the bubble we as a species have designed around ourselves breaks down for the selfless betterment of the system. South Park will be the epitome of Real Urbanism.

The structural integrity of all manmade materials has a lifespan—an inevitable failure. The decay of materials is an inherent process in all natural systems that manmade systems strive to transcend. Urban built typologies have varying lifespans, the shortest of which are known as soft sites due to their ease of development. In the South Park district of downtown Los Angeles, the existence of soft sites manifests in surface parking lots. Due to the materials of which these parking lots are made, these sites are poised for the adaptation of volunteer plant and animal species that thrive in urban areas. The continued decay of asphalt and concrete opens the layers of soil below to elements such as wind and precipitation. These processes will regenerate the soil over time to allow for a greater diversity of plant and animal species to exist as the health of the soil reaches acceptable levels.

When the benefit of the integration of urban and natural systems is realized, the focus of development will shift to support this adaptation on an administrative level. The average size of apartments and lofts will decrease drastically inside to allow for a larger takeover of natural systems, while still allowing for an incredibly high human population. As the decay of surface materials continues to adjacent roads and streets, the former programming of surface parking lots become obsolete as the infrastructure that feeds them can no longer support the systems for which they were designed. South Park becomes the truest of walkable communities.

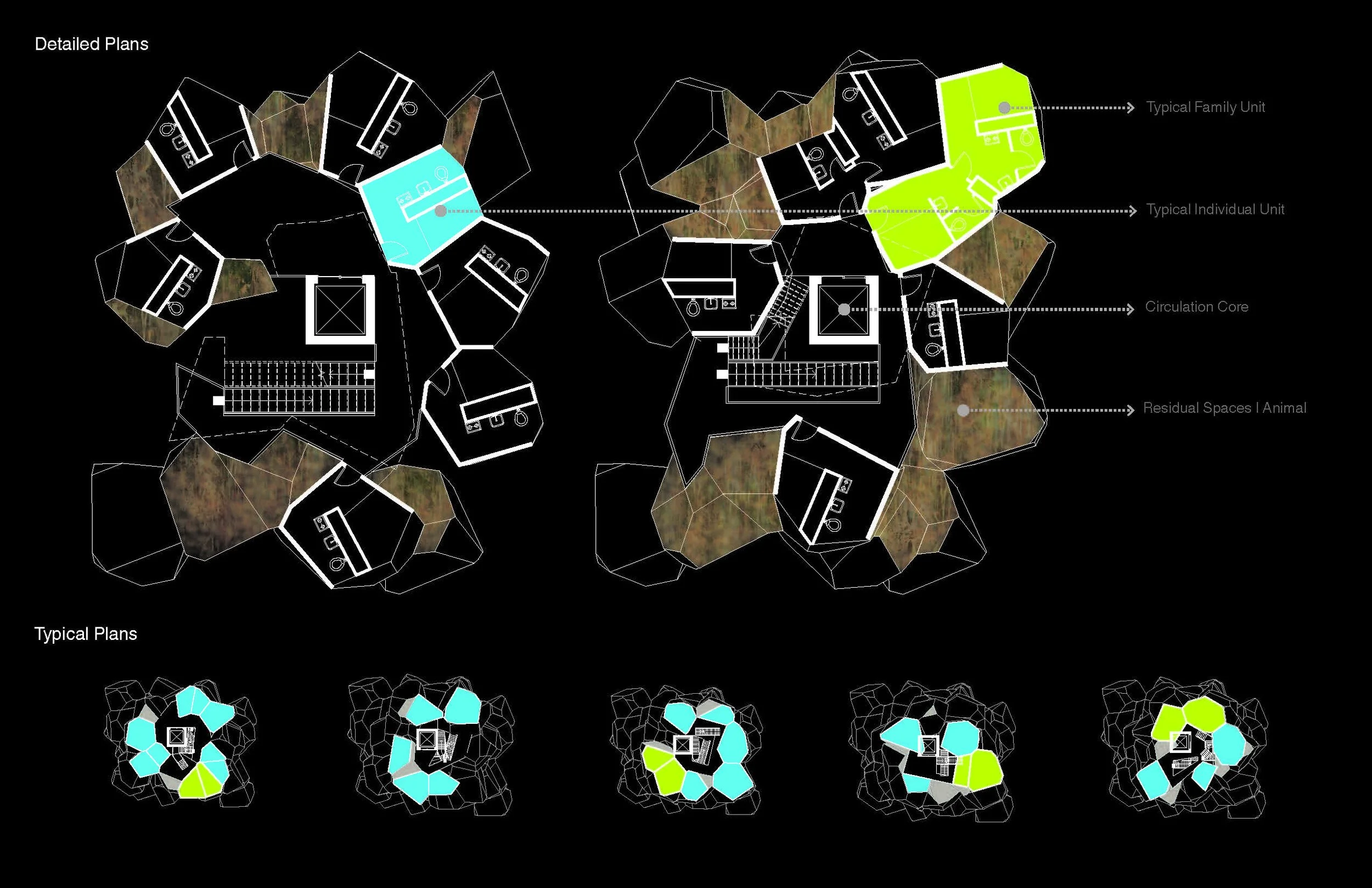

Since it is humans that realize the benefits of allowing deer, rodents, insects, small mammals, and many other species to exist in their communities, humans will be the ones to construct the built form that facilitates growth, adaptability, and decay—this is not a self-replicating system. The architecture of South Park encapsulates modularity, interconnectivity, change, and opportunity. The entirety of proposed architectural development is an agglomeration of individual cells based on the necessary space for a human occupancy. A living room is not a necessity. Walk in closets are not a necessity. This cell provides space for the most basic of human functions: eating, sleeping, and excreting. All other activities pertaining to human culture, society, interactivity, and personal fulfillment occur outside of the cell in the entirety of the public realm.

The inclusion of such a large density of plant and animal species requires many new professions that do not normally exist in the city—some of these professions will be filled by symbiotic species other than humans. Waste and debris from producer species will be broken down and used by consumer species. The products of plants and animals will be harvested by humans as well as other animals as needed. These professions are just as opportunistic as the species that serve them. Physical space for these activities will occur in the easiest of places. In South Park, these can happen in three different ways: within the voids created by proposed architecture, inside of existing structures, and on the street. The architecture exists as a shell that envelops a phonological hive of plants, animals, and infrastructure. The remaining space within allows for workshops, stores, and gathering spaces for humans. As the new architecture grows and attaches to existing structures, the uses for on-site building may not necessarily function with proposed programming. Therefore existing structures will adapt to provide space for larger urban operations. The street exists as the primary public space. Since cars no longer dominate the South Park landscape, the facilitation of market stalls, butcher shops, and waste collection are the preferred program elements of the streetscape.

Coexistence and codependency are values necessary for this type of proposed urbanism to succeed. Too often is “nature” excluded from the human environment when in reality, natural systems are essential to life and cannot be fenced in. If we are to call projects “green” and “sustainable,” we need to understand the implications of these words. While there is a positive and productive side to the ideas present in conventional ecological urbanism, the energy and resources required are rarely considered and never visible to those who think it is beneficial.

This undergraduate landscape architecture capstone project was designed by the interdisciplinary design team of Yan Aung, Kevin Finch, Helen Kang, and Evan Lee in the Spring Quarter of 2012. This studio was written and taught by the interdisciplinary team of Luis Hoyos, Barry Lehrman, Deborah Murphy, Phillip Pregil, Andy Wilcox, and Allyne Winderman.